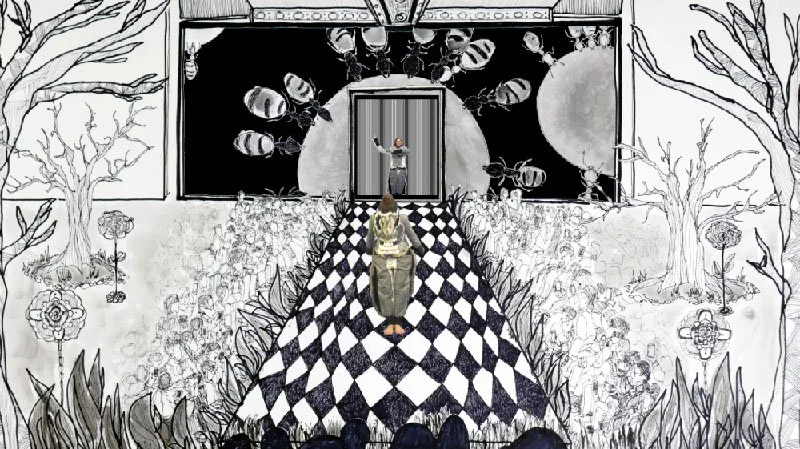

The final zoom event on December 27, 2020 culminated our experiments with Tango movements and attempts to integrate them with aricoco’s personal fear of insects, her contradictory interest in social insect colony, and basic scientific knowledge of Division of Labor in ant society gleaned from communicating with a biologist.

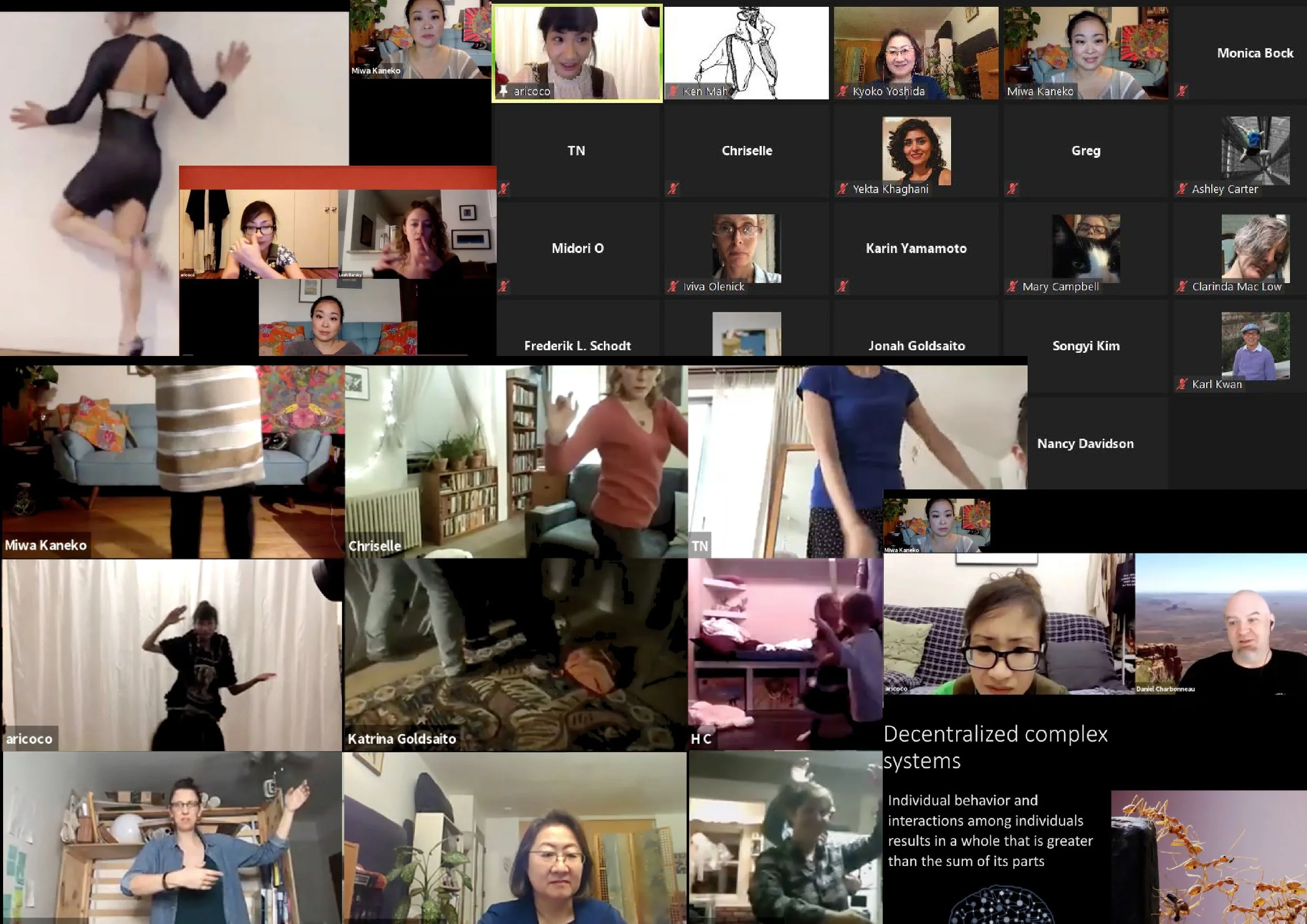

During the zoom event, we streamed a video of virtual runway-performance show, featuring participants’ Tango-inspired performances that were recorded and collected via zoom meetings. The video introduced a series of uniforms created by aricoco, that were tailored to fit the needs and roles of insect-human hybrid colony members whose specialized tasks were divided according to Division of Labor. Following the video screening, Miwa led a “virtual milonga (Tango dance party)”, where audiences were invited to try some Tango moves. During the “milonga”, there was a short Tango Barre performance (pre-recorded video) by Leah Barsky. Subsequently, aricoco performed her new piece live from her living room…

Leading up to realization of this event, aricoco and her collaborator Miwa created several online programmings including, streaming of Tango follower’s step instruction video (led by Miwa), zoom workshops by our contributor, Leah Barsky (Professional Tango dancer) and her interview video, and interview with a biologist, Dr. Daniel Charbonneau. Those recordings (except the zoom workshops by Leah) are available for viewing - Scroll down to find links below!

This project was made possible in part with public funds from Creative Engagement, supported by the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council and administered by LMCC.

Tango followers basic steps by miwa kaneko

Interview with leah Barsky

Interview/Lecture of biologist, Dr. Daniel Charbonneau

The video was streamed on YouTube on Sunday September 6, at 4pm EST.

At the time of the interview, Dr. Daniel Charbonneau was a Postdoctoral Research Scholar at Arizona State University.

"When I was a kid, I was very interested in animals, dinosaurs and pretty much anything to do with natural history. I spent countless hours poring over this massive atlas of plants and animals we had at my house. I still vividly remember the illustrations of pre-Cambrian plants, leopards lazily resting in trees, and all the strange animals I’d never heard of or imagined I’d ever see, like armadillos and anteaters. At the time, I wasn’t especially interested in insects, though I did dig up my fair share of back yard ant colonies; attempting to keep them in plastic soda bottles, not understanding that just like those ant farms you could buy, they didn’t have a queen and the colony would die out pretty quickly.

During my teen years, my interests veered more towards technology, electronics, and computers which led to my pursuing a degree in computer science and engineering. As part of my degree, I ended up taking a biology course that fully reignited my fascination with the natural world. My teacher was phenomenal and had spent most of his career doing field work in marine biology, working with deep sea fish, sharks and dolphins. Going to class was more like witnessing the behind the scenes of a nature documentary than a lecture. I was hooked and immediately changed my focus to biology.

While studying biology, I began to see connections between my understanding of computer systems and biological systems as complex systems where the interaction between each component produces a whole that’s greater than the sum of its parts. However, none was more fascinating than social insect societies that have this entire additional level of complexity within each colony. These societies that seem to mirror our own human societies, and yet can also be strikingly different. These societies whose function seems to mimic human brains and computers in their capacity to process information and ‘think’.

The worldview that I came away with and the lines of inquiry that derived from it led me to pursue a PhD studying the organization of social insect colonies. Once I began diving into the way that social insect colonies organized work, allocated tasks and divided labor, one of the most striking bits of information I came across was that, contrary to our notion that social insects are these super productive societies, seemingly the majority of individuals in a colony actually appear to be doing nothing in particular. Simply standing around while other workers go about their work. And so, that became the focus of my thesis, and ultimately the focus of my ongoing and future research. " - Daniel Charbonneau